|

|

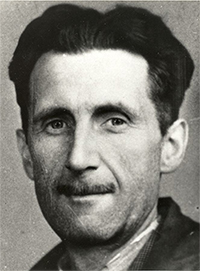

George Orwell Press Photo

|

Thursday, April 30, 2020

There are a lot of really good sentences in the book Animal Farm, George Orwell’s allegorical account of totalitarianism in which two ambitious pigs—Napoleon and Snowball—lead the rest of the farm animals in a revolt against their human overseers. But perhaps the most famous sentence is this one:

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.[1]

As satire, this sentence offers a biting critique of a falsely fair system. If, however, we modify it slightly, we can get a helpful way to think about time management, particularly as people continue to adjust to the new schedules and work environments that the coronavirus has created. That modification goes like this:

All hours are equal, but some hours are more equal than others.

On one level, yes, all hours are equal. They all have 60 minutes. But on a different level, some hours are more equal than others. The hour between 7:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. is worth a lot more to a morning person than it is to a night owl. And the hour after lunch can be a productivity dead zone for some people, but for others that same time may be when they really hit their cognitive stride.

So think about the hours during which you produce your best work, especially when it comes to intellectually tasking activities like writing and editing. Then, almost like you are acquiring assets, try to save as many of them as possible for your most important projects, whether professional, personal, or some combination of the two.

One idea for how to do this comes from the book Art Thinking: How to Carve Out Creative Space in a World of Schedules, Budgets, and Bosses. It was written by Amy Whitaker, who teaches at New York University and holds an interesting combination of degrees. She has an MFA in painting from University College London and an MBA in strategy from the Yale School of Management. So she’s artistic, but she’s also really pragmatic. Here’s how she describes the aim of the book, after noting that creativity and commerce are extremely intertwined:

[Art Thinking] is about how to construct a life of originality and meaning within the real constraints of the market economy. It is about how to make space for vulnerability and the possibility of failure within the world of work, with its very real and structural pressures to get things done, to win praise and adulation, and to contribute to bottom-line growth.[2]

Whitaker suggests making it a point to regularly have “studio time,” which she defines as a time to indulge your curiosity. “Do anything you want with that time,” she said in an interview with the Financial Times in 2016. “The point is to give yourself ritualized time and space to learn and do.”[3]

An important characteristic of studio time for Whitaker is that it be a safe place to experiment and fail. But I have found that the idea of consistently building in protected amounts of time for yourself can help with high-stakes projects as well. I know litigators who use versions of studio time to work on important briefs, even going so far as to schedule recurring meetings with themselves to make sure they have sufficiently big chunks of their day blocked off. I know judges and professors and CEOs who do something similar.

Each of them is intentional about what Georgetown University computer scientist Cal Newport calls “deep work,” which he defines as “[p]rofessional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.”[4]

Newport contrasts this with “shallow work”: “Noncognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.”[5]

You don’t need studio time for shallow work. You can do that between meetings, while commuting, maybe even while waiting in line. But for your difficult, high-value projects, consider Whitaker’s idea, even if it is just to set up a mental studio.

You don’t need a smock. You don’t need an easel. You simply need a consistent commitment to focusing your attention—and your schedule—on something that is important and, ideally, edifying.

Perhaps that something will even turn out to be as insightful and well-crafted as Animal Farm. That would be a nice, much more positive way, of being Orwellian.

Patrick Barry is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Michigan Law School and a visiting lecturer at the University of Chicago Law School. He is the author of Good with Words: Writing and Editing, The Syntax of Sports, and the forthcoming series Notes on Nuance. Thanks to Nicholas Dawson and Ingrid Yin for their excellent research and editing help.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons. Last edited November 23, 2016. Public Domain.

Articles that appear on michbar.org do not necessarily reflect the official position of the State Bar of Michigan and their publication does not constitute an endorsement of views which may be expressed.

[1] Orwell, Animal Farm (New York: Signet, 1996), p 112.

[2] Whitaker, Art Thinking: How to Carve Out Creative Space in a World of Schedules, Budgets, and Bosses (New York: HarperCollins, 2016), p 5.

[4] Newport, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2016), p 3.