Abe Lincoln. Atticus Finch. The myth of the “country lawyer” runs deep in America. As one scholar described the stereotypical depiction:

Everyone knows what a “country lawyer” looks like. He (it’s always a “he”) is middle-aged or older, an avuncular mix of wisdom and good humor. He is a generalist, in a small town, deeply connected to his community. He is trusted and respected. The person who is called upon when trouble threatens.1

He (it’s always a “he”) is middle-aged or older, an avuncular mix of wisdom and good humor. He is a generalist, in a small town, deeply connected to his community. He is trusted and respected. The person who is called upon when trouble threatens.1

Like most myths, there is a foundational truth at the core. Rural attorneys played key roles in communities across the nation. And some have speculated that these real-world lawyers, tied tightly to local communities, contributed positively to the image of lawyers as people to be trusted, honest brokers, and upstanding professionals.2 Sure, those lawyers were paid, but clearly the practice of law was conducted less like a business than it is today.

As our economy grew and became more specialized, so, too, did the legal profession. More than 70 years ago, this was noted by Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, who relayed a story attributed to Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone:

Chief Justice Stone made an address some years ago which I would recommend that lawyers read from time to time. He pointed out there the changes that had resulted in society, and that lawyers should recognize that those changes had occurred. There were times, as in the little village from whence I came in Alabama, when the country lawyer took clients as they came. He did not know who the next client would be. There are some lawyers like that, of course, today; but Chief Justice Stone pointed out that as the economy of our society had changed there had been corresponding changes on the part of the legal profession. Lawyers had become specialists, precisely as business had been specialized. He pointed out that there were many firms in the country — not in criticism, but in recognition of the existing facts — which acted more on the basis of mass production.3

Things haven’t gotten better since Justice Stone’s remarks. As large-firm practice has evolved, as attorney specialization has increased, and as mobility away from one’s home has become easier and more commonplace, rural America has been left without lawyers. In modern parlance, the phrase is “legal deserts,” defined by the American Bar Association as counties with fewer than one attorney per 1,000 residents. South Dakota tried to tackle the problem in 2012 by actually paying lawyers to live in rural communities.4 The ABA held a major program in 2020 on the issue.5 At a recent conference I attended of bar leaders from across the country, about half were actively analyzing the issue and what to do about it. Illinois has been particularly active in this space.6

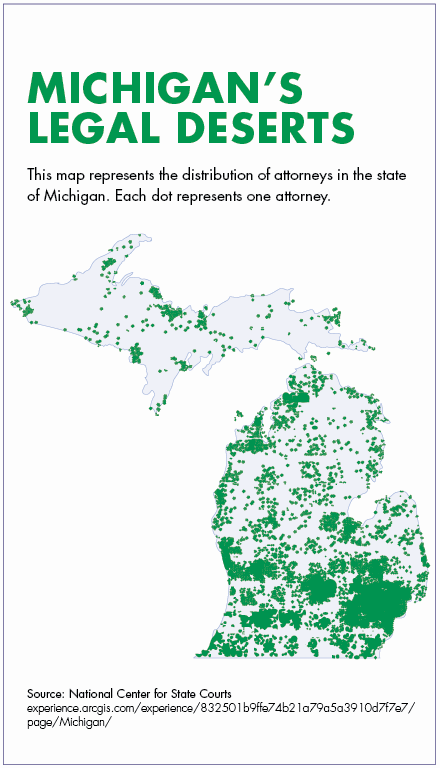

Michigan is not unique. The state’s population has remained essentially flat for the last 20 years7 and so has the number of active attorneys (in 2022, 35,001 reside in Michigan.)8 But those attorneys are more and more concentrated in our urban areas. In October 2023, the National Center for State Courts issued a report with compiled data to help Michigan target geographic areas with the greatest number of barriers to legal resources. Interactive maps help illustrate the areas of greatest need based on indicators of risk factors such as a limited number of attorneys compared to the population, long drive times to the courthouse, poverty, limited English proficiency, and lack of internet and/or broadband availability.9

Look at the map below. It tells a basic story: rural areas, which also have relatively high poverty rates and low internet accessibility, also lack local lawyers.

The State Court Administrative Office is working with the State Bar of Michigan and other stakeholders to increase the number of attorneys working in these legal deserts. As part of the broader civil access to justice issue in our state, the Supreme Court’s Justice For All Commission also is developing recommendations that will help ameliorate the absence of the rural attorney whether through better self-help mechanisms, easier and more user-friendly courts, or the ability in limited areas for non-attorneys to assist clients in navigating the legal system.

But these steps will not fully make up for the absence of local attorneys in rural communities. I do not think it is wistfully nostalgic to emphasize that actually having lawyers in these locales is valuable on many levels. Nor should it be understated that living in these communities provides a rich life, precisely the sort of work-life balance sought by newer generations of lawyers or perhaps more senior lawyers looking to jump off the hamster wheel of big-city practice.

The Bar will continue to focus on this issue and consider potential solutions; my friend and fellow SBM Commissioner Suzanne Larsen (from Marquette) is already rolling up her sleeves. She rightfully notes this is (at least) a two-pronged problem: how to get attorneys to practice in rural areas and how to support the unique needs of rural practitioners so they can provide a high level of legal service for the population they serve. Stay tuned for more to come on this important issue.

If this is important to you, let us know and get involved.