Have you seen the reel that shows a man ironing, turning off the iron, unplugging the iron, returning three times to see the iron unplugged, touching the cord and plug to confirm it is unplugged, and taking a picture of the unplugged cord? It’s funny … but not really.

This is a coping mechanism for anxiety. Admittedly, I have done all those things — except taking the photo, but only because I hadn’t thought of documenting it for later. Without this coping mechanism, and sometimes with it, the thought of my house, my neighbor’s house and the entire neighborhood on fire can haunt me all day. On good days, I can control my thoughts. On bad days, I can’t stop the flood of what-ifs. The reel is relatable for too many of us.

Lawyers are not immune to the struggles of depression, anxiety and substance use issues. In fact, the legal profession has increasingly become synonymous with chronic stress, burnout, mental health issues, and substance use challenges. Lawyers are expected to be sharp, resilient, and available at all hours — solving complex problems under pressure. Behind our impressive titles and legal victories, a quiet reality looms over the profession: many of us are running on empty.

The American Bar Association’s Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs and the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation’s 2016 study of nearly 13,000 practicing attorneys revealed high rates of mental health and substance use concerns:1

- 28 percent of lawyers suffered from depression.

- 19 percent of lawyers had anxiety.

- 11.5 percent of lawyers had suicidal thoughts at some point during their career.

The greatest rates of depression, anxiety, and problematic drinking were among attorneys in their first 10 years of practice.2 A 2021 survey of law student well-being3 reported additional concerning statistics, all of which had increased since a similar 2014 survey:

- 69 percent of law students needed emotional or mental health help in the past year 33 percent of law students had been diagnosed with depression

- 40 percent of law students report being diagnosed with anxiety

- 11 percent of law students report having suicidal thoughts in the last year

The ABA helped launch a follow-up well-being survey this year and we are expecting the results of that survey early next year. (Thank you to  all the Michigan attorneys who participated!)

all the Michigan attorneys who participated!)

The numbers tell us what we already know: We need help.

We are not taking care of ourselves, and it is literally killing us! The fact is that attorneys are six times more likely to complete suicide than the general public.4 Our profession and the responsibility we bear is taxing, often relentless. The toll it takes on our mental health, our families, and our well-being is real. The truth is: We cannot effectively serve others, if we do not first care for ourselves.

It is clear we must address this crisis.

MICHIGAN AT THE FOREFRONT

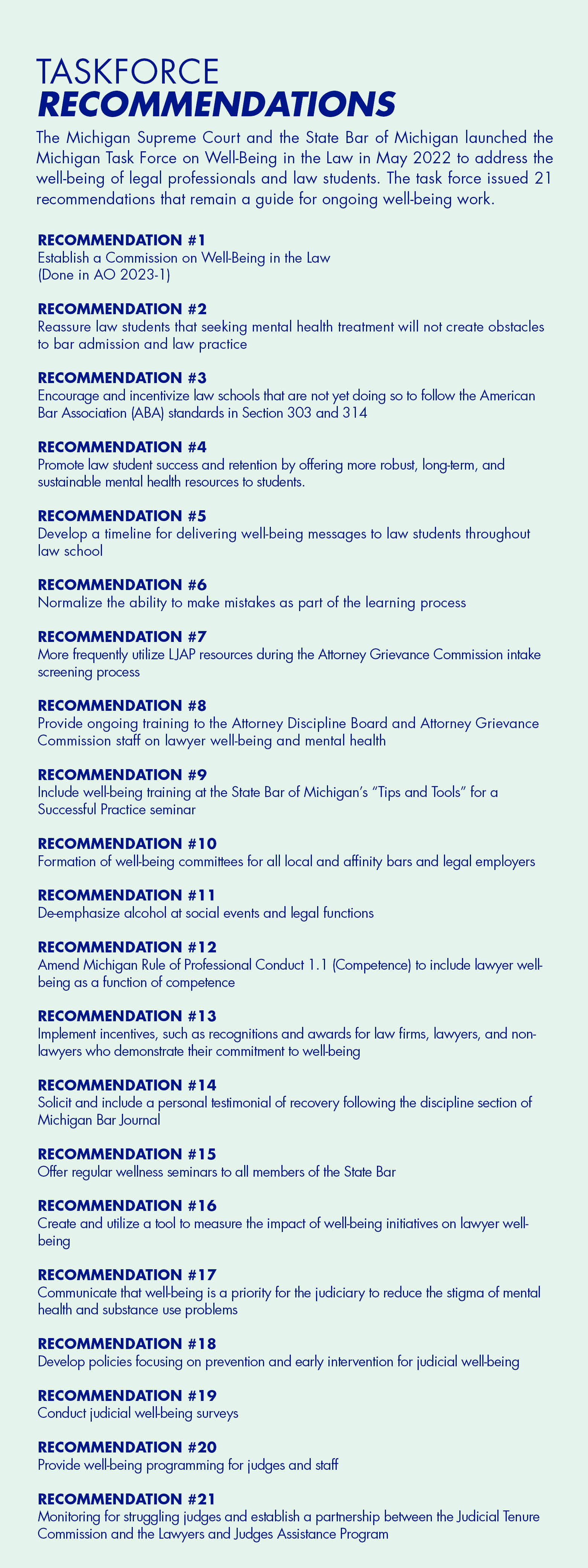

Recognizing the scope of the problem, the Michigan Supreme and the State Bar of Michigan jointly launched the Michigan Task Force on Well-Being in the Law in May 2022 to address the well-being of legal professionals and law students.5 The Task Force was comprised of 35 stakeholders with a wide range of perspectives, including representation from the Michigan Supreme Court, the State Bar of Michigan, the judiciary, lawyers, law schools/students, court administrators, regulators, tribal courts, and mental health professionals.

“Michigan’s legal community must understand that well-being is an essential component of competence and must do its part to foster an environment that encourages each member of the legal profession to strive for greater mental, physical, and emotional health.”6

— Michigan’s Task Force on Well-Being in the Law

After months of this important work, the Task Force issued its Report and Recommendation in August 2023, which is available online on the court’s website.7 There are 21 recommendations in the report directed at law students, practitioners and judicial officers. The first recommendation was to establish a commission on well-being in the law, which the Michigan Supreme Court did one month later with Administrative Order No. 2023-1: Creation of the Commission on Well-Being in the Law (WBIL).8

Under the guidance of co-chairs Chief Justice Megan Cavanagh (now Justice Kyra Bolden) and Molly Ranns, director of the State Bar of Michigan’s Lawyer and Judges Assistance Program, the Commission was created to lead the efforts to institute change by implementing the Task Force’s remaining recommendations. (Full disclosure: I also serve on the commission.)

The commission’s purpose is to “build upon the good work already accomplished by the Task Force and continue the forward momentum to change the climate of the legal culture by promoting well-being within the legal profession. The commission will foster an environment that encourages members of the legal profession, law students, and court staff to strive for greater mental, physical, and emotional health.”9

The commission created three workgroups:

- Incentivizing Well-Being: To encourage members of legal community to prioritize well-being and self-care. Rewarding and celebrating those who are embracing the opportunity to improve.

- Prevention and Promotion: To foster a supportive and resilient legal community by providing comprehensive education and resources to mitigate the stressors associated with the legal profession. Through targeted initiatives, we aim to:

- Educate law students, practitioners, and judges on the common challenges faced throughout their legal journeys.

- Identify and address pressure points and susceptible intervals that can contribute to stress and burnout.

- Promote healthy coping skills and strategies to enhance well-being and resilience.

- Normalize the experience of stress within the legal community, fostering a culture of understanding and support.

- Create a more sustainable and fulfilling legal profession by empowering individuals with knowledge and tools.

- Well-Being Programming: To promote and support well-being in the legal profession by providing access to comprehensive education, counseling, and training programs that empower legal professionals to prioritize their mental, emotional, and physical health. We aim to create lasting buy-in through open dialogue, destigmatizing wellness challenges, and increasing accessibility to resources. By integrating well-being initiatives into existing professional development programs, we foster a sustainable culture of holistic well-being that enhances both personal fulfillment and professional excellence within the legal community.

Fortunately, our state is at the forefront of change. In addition to the State Bar of Michigan, through its collaborations and through its Lawyers and Judges Assistance Program, many local and affinity bar associations, and law firms are beginning to prioritize lawyer well-being as part of their professional development and organizational culture. Flexible working policies, mental health resources, and mindfulness or resilience programs are becoming more common.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

“As one person, I cannot change the world, but I can change the world of one person.”

— Paul Shane Spear

Change is long overdue in the legal profession. We need to get out of our own way and acknowledge that mental health is not merely an issue affecting the weak — it affects us all. We must prioritize mental health, work-life balance, and mentorship, especially for young and diverse lawyers entering the field. To do this, we must individually and collectively work to eliminate the stigma associated with mental health, recognize and learn how to respond to help-seeking behaviors, and redefine what success looks like.

Eliminate the Stigma

I wrote earlier about developing coping mechanisms when anxiety strikes, such as taking that photo of the unplugged iron. I speak from experience. I suffered through anxiety for many years … alone. I was terrified that seeking the help I desperately needed and wanted would derail my future — whatever it might be. Instead, I developed coping mechanisms.

It started simple: First, I would try to identify the worst-case scenario and then respond to it. Using the iron example, the worst that could happen if it was left on is that my house could burn down. Then I would find comfort in knowing that is why I have insurance. (I didn’t have dogs at the time.) While this coping mechanism helped, I also knew I needed help. Unfortunately, it took many years for me to find the courage to seek help and even after I did, I still feared for years that it would derail my future. I know and understand today that getting help made me a better, stronger attorney, and in fact helped me build my career. I only wish I had come to that realization sooner.

I suffered in silence for no reason.

Some may condemn my decision to share my struggles, but if sharing my struggles encourages just one person reading this article to seek the help that they want and need, without fear of negative implications, then I’ve done my part.

Recognize Help-Seeking Behaviors and Learn How to Respond

We are all struggling to some degree — but often are afraid to talk about it. You can help your friend, colleague or bench-mate by being able to identify when someone is reaching out for help, either directly or indirectly, and responding in a way that supports their needs.

Direct indicators include expressing one’s feelings of being overwhelmed, stressed, depressed, anxious or needing help. A few indirect indicators of help-seeking behavior include: shifts in personality, such as excessive drinking, withdrawing, or engaging in risky behavior; changes in routine, such as sleeping more or less, neglecting personal hygiene, or ceasing gym attendance; negative self-talk; and seeking reassurance or support more frequently.

When you recognize help-seeking behaviors, be ready and willing to listen, offer empathy, avoid judging or shaming, normalize seeking help, offer resources such as therapist recommendations, and be sure to follow up — a quick text telling the person that you’re thinking about them can go a long way.

Recognizing these signs is vital because often people won’t openly ask for help unless they feel safe. Being attentive and sensitive to the subtle signs of distress can provide the encouragement they need to take the next step toward healing.

Redefining what Success Looks Like

Sustainable transformation requires leadership commitment. Leaders and educators must normalize discussions about mental health, model healthy behaviors, and reconsider performance metrics that reward excessive hours over quality of work. For generations, success in the legal profession has been measured by billable hours, law firm rankings, and courtroom victories. Leaders must emphasis that true success must also include sustainability — the ability to thrive, not just survive, in one’s career. Law schools also bear responsibility for embedding well-being and resilience into curricula as core professional skills.

Real progress requires more than policies. It needs a mindset shift. Senior partners and firm leaders play a crucial role in setting the tone. When leaders openly discuss mental health, take time off without guilt, and encourage balance, they give others permission to do the same. Well-being isn’t just a personal issue; it’s a leadership responsibility.

Well-being doesn’t mean working less or caring less. It means working smarter, with purpose and perspective. It means acknowledging that lawyers are human first, and that a healthy mind is a sharper, fairer, and more effective one.

CONCLUSION

A thriving legal community depends on professionals who are engaged, healthy, and fulfilled. We cannot effectively serve others, if we do not first care for ourselves — with the same dedication, integrity, and care we give our clients.

I close by asking all my colleagues to please do your part to help end the stigma around mental health and to speak openly about the importance of mental health, work-life balance, and wellness in our profession.